From watercoolergames, Wolves Evolve, and VirtualPolitik comes the astonishing news that the estate of Guy Debord has issued a cease and desist to Alex Galloway for his Radical Software Group’s recent implementation of Debord’s Game of War (Kriegsspiel).

As woeful and bizarre as I find that news, the ensuing discussion in the blogs and comments has manifested some terminological confusion over the use of the word Kriegsspiel (the title Galloway employs for Debord’s Le Jeu de la Guerre, A Game of War).

Kriegsspiel, of course, is German for (literally) “war game.” In 1824, the Prussian staff officer Georg von Reisswitz formally introduced the game (versions of which had been kicking around in his family for years) to his fellow officers. (“This is not a game! This is training for war!” one general is said to have exclaimed.) It was quickly adopted, and became the foundation for the German use of wargaming which persisted through World War II (these are the “sand table exercises” of which Friedrich Kittler writes in his cryptic preface to Grammaphone, Film, Typewriter). Some, however, have interpreted the tradition of the German Kriegsspiel and Debord’s apparent use of the same title as evidence that Debord’s game is itself a derivative work, and that Galloway’s implementation of it is simply another instance of the game’s progression since the early 19th century.

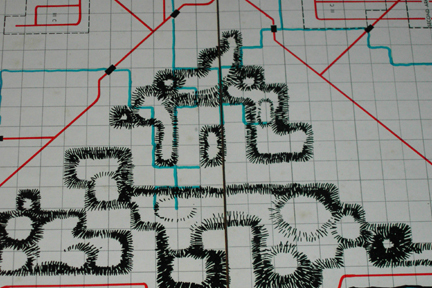

Unfortunately, this is factually incorrect. The von Reisswitz Kriegsspiel was played by laying metal bars across maps to mark troop dispositions. By the middle of the 19th century, it had evolved two major variants, so-called “rigid” and “free” Kriegsspiel. The latter attempted to replace the elaborate rules and calculations of the game with a human umpire who makes decisions about combat, intelligence, and other aspects of the battlefield. Kriegsspiel is thus the title of a loose family of military map exercise games, which emerged and evolved throughout the 19th century. (The authoritative account of the origins and development of Kriegsspiel as I have been recounting them here is to be found in Peter Perla’s excellent The Art of Wargaming [Naval Institute Press, 1990].)

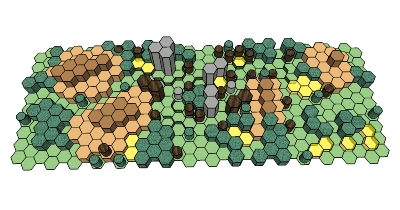

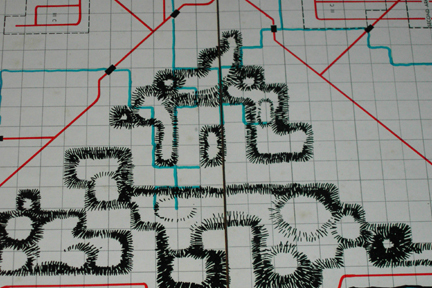

Debord’s game bears only the vaguest generic resemblance to the tradition of Prussian Kriegsspiel. The Kriegsspiel was played on actual military topographical maps, often of terrain that was anticipated as the scene of future conflict (for example, the Schlieffen plan was subject to extensive rehearsal as a Kriegsspiel, using contemporary maps of the Ardennes). Debord’s game, by contrast, is played on a gridded board that depicts two abstract nations or territories, more or less symmetrical in terms of geographic features.

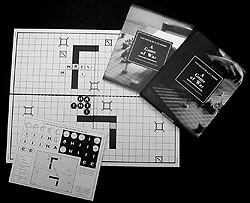

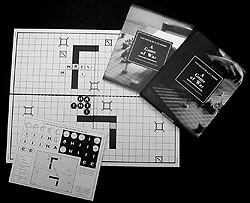

Above is a small section of the so-called “Meckel map,” the 1:7500 map set that became canonical for play of early Kriegsspiel, alongside of the 2007 Atlas Press print edition of Debord’s game.

Debord’s game actually bears a much closer resemblance to the tradition of commercial board wargaming I write about here on ZOI. I have no idea (or way of knowing) whether Debord was familiar with these games himself, but there are family resemblances worth pointing out. In 1958, Charles S. Roberts founded the Avalon Hill Game Company to publish his military game products, the first of which was called Tactics II. It is a generic conflict game between two abstract combatants, red and blue. Alongside of games on specific historical battles and campaigns (like Gettysburg, which came out the same year) Roberts and others in the emerging hobby published occasional abstract conflict games which sought to model the essence of warfare. Here, for example, is portion of the board for Tactics II, which shows a “mountain pass” (also a key terrain feature in Debord’s game):

There are some important differences, however, between Roberts’ designs and Debord’s. Roberts introduced the use of the Combat Results Table, basically a Monte Carlo table with a distributed set of outcomes based on odds ratios of the combatants. To resolve an engagement, players tote up the odds of the forces involved, add modifiers or column shifts for terrain and the like, then roll a die and consult the table to determine the outcome. In Debord’s game, by contrast, combat is deterministic. One calculates the total number of offensive and defensive points that can be brought to bear on a contested grid square, and based on those numbers the defending unit either retreats, is eliminated, or holds its ground. Nothing is left to chance.

Debord’s game also no doubt owes something to the tradition of chess variants that were popular throughout the 20th century, including the “Kriegsspiel” variant that John von Neumann famously enjoyed, in which play proceeds in a double blind manner (neither player is aware of the location and position of his opponent’s forces). Or else consider a 1933 Soviet military variant by A.S. Yurgelevich: “The game is played on a board of 128 squares, obtained by adding to all four sides of a regular eight by eight board a strip of two by eight (or eight by two) squares. Players have each twenty-four pieces: a headquarter, a bomber, a tank, two guns, two cavalry, two machine-guns, and fifteen soldiers.”

(Thanks to Peter Bogdasarian for this reference.)

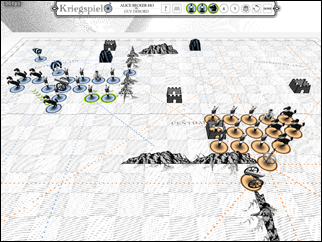

A final note. Alex Galloway, in his writing about Debord’s Game of War, makes much of the “rhizomatic” nature of the all-important lines of communication that govern each side’s ability to move and fight their pieces:

[A] sympathetic reading of Debord would be to say that the lines of communication in the game are Debord’s antidote to the specter of the nostalgic algorithm. They are the symptomatic key into Debord’s own algorithmic figuration of the new information society growing up all around him. In short, Kriegspiel is something like “Chess with networks.â€

Perhaps. But it’s worth noting, that while absent from games like Chess and Go, such lines of communication had been a standard feature of commercial board wargames in Roberts’ tradition since at least the 1968 (fateful year) publication of James Dunnigan’s 1914, a strategic level game on the First World War. As typically expressed, the mechanic requires units to be “in supply” or else suffer grievous consequences. Being in supply means being able to trace a line of contiguous hexes, free from enemy units or their “zones of control” to a friendly map edge or supply depot. In practice, this sometimes required excessively “gamey” tactics, as players would trace elaborate looping lines of supply, skirting enemy units to eventually corkscrew around back to their own rear areas. Debord’s lines of communication are much less forgiving, their hard geometries undeniably evoking something of the grid or the matrix that feels very contemporary (Gibson’s “lines of light” in the non-space of cyberspace).

It would be fascinating to know what, if any, contact Debord has with board wargames from companies like Avalon Hill and SPI. We know, says Galloway, that he played political strategy games like Djambi. Board wargames enjoyed similar public popularity during the time when Debord was developing his Game of War, and it is not inconceivable that he would have encountered them.

Others can comment with more authority than I on the ultimate legal merit or lack thereof of the cease and desist. I can say that Debord’s game, while not much in the tradition of classic Prussian Kriegsspiel, does bear some resemblance to other commercial wargame designs then popular in the marketplace. All games, it seems to me, emerge from a thick tissue of tradition and ideas, and it would be a shame indeed if Debord’s work was denied this revival of interest over tired matters of originality and “infringement.”

Â Â Â Â Â