On Debord’s Kriegsspiel and Board Wargames

From watercoolergames, Wolves Evolve, and VirtualPolitik comes the astonishing news that the estate of Guy Debord has issued a cease and desist to Alex Galloway for his Radical Software Group’s recent implementation of Debord’s Game of War (Kriegsspiel).

As woeful and bizarre as I find that news, the ensuing discussion in the blogs and comments has manifested some terminological confusion over the use of the word Kriegsspiel (the title Galloway employs for Debord’s Le Jeu de la Guerre, A Game of War).

Kriegsspiel, of course, is German for (literally) “war game.” In 1824, the Prussian staff officer Georg von Reisswitz formally introduced the game (versions of which had been kicking around in his family for years) to his fellow officers. (“This is not a game! This is training for war!” one general is said to have exclaimed.) It was quickly adopted, and became the foundation for the German use of wargaming which persisted through World War II (these are the “sand table exercises” of which Friedrich Kittler writes in his cryptic preface to Grammaphone, Film, Typewriter). Some, however, have interpreted the tradition of the German Kriegsspiel and Debord’s apparent use of the same title as evidence that Debord’s game is itself a derivative work, and that Galloway’s implementation of it is simply another instance of the game’s progression since the early 19th century.

Unfortunately, this is factually incorrect. The von Reisswitz Kriegsspiel was played by laying metal bars across maps to mark troop dispositions. By the middle of the 19th century, it had evolved two major variants, so-called “rigid” and “free” Kriegsspiel. The latter attempted to replace the elaborate rules and calculations of the game with a human umpire who makes decisions about combat, intelligence, and other aspects of the battlefield. Kriegsspiel is thus the title of a loose family of military map exercise games, which emerged and evolved throughout the 19th century. (The authoritative account of the origins and development of Kriegsspiel as I have been recounting them here is to be found in Peter Perla’s excellent The Art of Wargaming [Naval Institute Press, 1990].)

Debord’s game bears only the vaguest generic resemblance to the tradition of Prussian Kriegsspiel. The Kriegsspiel was played on actual military topographical maps, often of terrain that was anticipated as the scene of future conflict (for example, the Schlieffen plan was subject to extensive rehearsal as a Kriegsspiel, using contemporary maps of the Ardennes). Debord’s game, by contrast, is played on a gridded board that depicts two abstract nations or territories, more or less symmetrical in terms of geographic features.

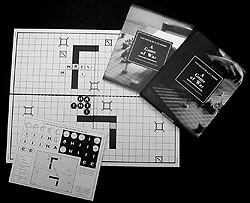

Above is a small section of the so-called “Meckel map,” the 1:7500 map set that became canonical for play of early Kriegsspiel, alongside of the 2007 Atlas Press print edition of Debord’s game.

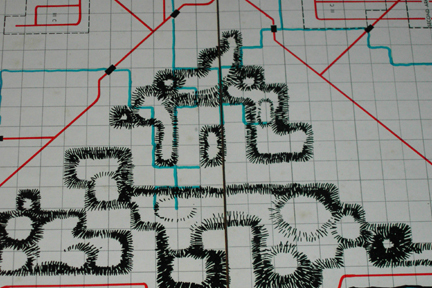

Debord’s game actually bears a much closer resemblance to the tradition of commercial board wargaming I write about here on ZOI. I have no idea (or way of knowing) whether Debord was familiar with these games himself, but there are family resemblances worth pointing out. In 1958, Charles S. Roberts founded the Avalon Hill Game Company to publish his military game products, the first of which was called Tactics II. It is a generic conflict game between two abstract combatants, red and blue. Alongside of games on specific historical battles and campaigns (like Gettysburg, which came out the same year) Roberts and others in the emerging hobby published occasional abstract conflict games which sought to model the essence of warfare. Here, for example, is portion of the board for Tactics II, which shows a “mountain pass” (also a key terrain feature in Debord’s game):

There are some important differences, however, between Roberts’ designs and Debord’s. Roberts introduced the use of the Combat Results Table, basically a Monte Carlo table with a distributed set of outcomes based on odds ratios of the combatants. To resolve an engagement, players tote up the odds of the forces involved, add modifiers or column shifts for terrain and the like, then roll a die and consult the table to determine the outcome. In Debord’s game, by contrast, combat is deterministic. One calculates the total number of offensive and defensive points that can be brought to bear on a contested grid square, and based on those numbers the defending unit either retreats, is eliminated, or holds its ground. Nothing is left to chance.

Debord’s game also no doubt owes something to the tradition of chess variants that were popular throughout the 20th century, including the “Kriegsspiel” variant that John von Neumann famously enjoyed, in which play proceeds in a double blind manner (neither player is aware of the location and position of his opponent’s forces). Or else consider a 1933 Soviet military variant by A.S. Yurgelevich: “The game is played on a board of 128 squares, obtained by adding to all four sides of a regular eight by eight board a strip of two by eight (or eight by two) squares. Players have each twenty-four pieces: a headquarter, a bomber, a tank, two guns, two cavalry, two machine-guns, and fifteen soldiers.”

(Thanks to Peter Bogdasarian for this reference.)

A final note. Alex Galloway, in his writing about Debord’s Game of War, makes much of the “rhizomatic” nature of the all-important lines of communication that govern each side’s ability to move and fight their pieces:

[A] sympathetic reading of Debord would be to say that the lines of communication in the game are Debord’s antidote to the specter of the nostalgic algorithm. They are the symptomatic key into Debord’s own algorithmic figuration of the new information society growing up all around him. In short, Kriegspiel is something like “Chess with networks.â€

Perhaps. But it’s worth noting, that while absent from games like Chess and Go, such lines of communication had been a standard feature of commercial board wargames in Roberts’ tradition since at least the 1968 (fateful year) publication of James Dunnigan’s 1914, a strategic level game on the First World War. As typically expressed, the mechanic requires units to be “in supply” or else suffer grievous consequences. Being in supply means being able to trace a line of contiguous hexes, free from enemy units or their “zones of control” to a friendly map edge or supply depot. In practice, this sometimes required excessively “gamey” tactics, as players would trace elaborate looping lines of supply, skirting enemy units to eventually corkscrew around back to their own rear areas. Debord’s lines of communication are much less forgiving, their hard geometries undeniably evoking something of the grid or the matrix that feels very contemporary (Gibson’s “lines of light” in the non-space of cyberspace).

It would be fascinating to know what, if any, contact Debord has with board wargames from companies like Avalon Hill and SPI. We know, says Galloway, that he played political strategy games like Djambi. Board wargames enjoyed similar public popularity during the time when Debord was developing his Game of War, and it is not inconceivable that he would have encountered them.

Others can comment with more authority than I on the ultimate legal merit or lack thereof of the cease and desist. I can say that Debord’s game, while not much in the tradition of classic Prussian Kriegsspiel, does bear some resemblance to other commercial wargame designs then popular in the marketplace. All games, it seems to me, emerge from a thick tissue of tradition and ideas, and it would be a shame indeed if Debord’s work was denied this revival of interest over tired matters of originality and “infringement.”

Jon Ippolito said,

April 14, 2008 at 4:01 pm

Hi Matt,

Glad to see you touched on the “revival of interest”–of both the historical and, unfortunately, the monetary kind–generated by Galloway’s reinterpretation. What no other commentator has noticed is that it is only by such reinterpretations that we currently know many artifacts of history, and it is only by encouraging responsible reinterpretations that we may have any sense of a broad swathe of culture from this digital century.

jon

Matthew said,

April 14, 2008 at 6:17 pm

Jon,

Absolutely.

Mark Guttag said,

April 15, 2008 at 3:05 pm

Matt,

A very interesting article. I was familar with the history of Kriegspiel (from Peter Perla’s and other sources on the history of wargaming), but was not previously familar with Debord’s game.

I believe Charles Roberts’ original version of D-Day (1961) was probably the first commercial board wargame with supply trace rules. In fact, the game even had different supply capacities for the Allies depending on their invasion zone and the ports they captured.

Mark

Matthew said,

April 15, 2008 at 6:08 pm

Thanks, Mark. Glad to know about the 1961 D-Day.

Steffen P. Walz said,

April 16, 2008 at 4:52 pm

dear matthew,

thank you for your post, and – i assume – quasi reply to ian bogost’s original posting and my comment over at http://www.watercoolergames.org/archives/000915.shtml. pls note that i will post my following sermon over at ian’s and gonzalo’s, too.

i think you missed some of the slight irony i tried to package into my reply at WCG. thus, let me be a tad more explicit –

consider this: why do you think galloway & the RSG collective translate and distribute their digital implementation of debord’s game, which went by the french title of “le jeu de guerre”, into the german name of “kriegspiel” (a term which is, excuse my repetetiveness, grammtatically incorrect and a typo)? let’s see – because translating the term into german is, say: fun / appropriate / critical, or, as suggested over at WCG, situationism in itself?

in europe, we do carefully differentiate between languages, and french is not german, and german ain’t french. at least to me, language matters, and esp. titles do. why? because – excuse my lecturing tone – language is suggestive, emblematic, symbolic and a vehicle of power. i do not find any traces at http://r-s-g.org/kriegspiel/about.php as to why RSG chooses a german name for their (straightforward) port.

it is not the ominous “some” who have interpreted that debord’s game is a derivative work of reisswitz’s game, as you suggest; it is the RSG group whose german language game title suggests that this is the case. using a german name for an explicit port of debord’s game is, unfortunately, imprecise, and misleading, and not a straightforward port.

however, there is one acceptable exception: galloway & his group are making a statement. but then, this statement is, frankly, lost on me. the only western nation that has been waging war in the past couple of years, and the only nation that has been pioneering the public usage of “war” training video games is: yeah, right, english speaking. a decorum title of a digital port of debord’s game thence is “game of war”, a name which, by the way, mckenzie wark uses throughout his clever essay posted to the situationism blog at http://totality.tv/2008/4/13/game.

i can only hope that someone from RSG follows this discussion, too. i would love to see them involved in conversation.

take care,

spw

alex galloway said,

April 16, 2008 at 8:36 pm

greetings. the answer is a simple one: debord called his game the “kriegspiel” (with one ‘s’) in his notes and letters. it only received the name “le jeu de la guerre” later once it was fabricated and published.

+ + +

here is a useful quote from the RSG website:

In his letters Debord referred to the game as the “Kriegspiel,” borrowing the German term meaning “war game.” When the game was fabricated and released in France, Debord officially titled it “Le Jeu de la guerre.” Since the phrasing “The Game of War” is slightly awkward in English, we opted to title the RSG game using the original word favored by Debord: Kriegspiel.

(from http://r-s-g.org/kriegspiel/about.php)

+ + +

and here is some further background from the RSG “errata” page:

A short discussion on the most appropriate translation of the game’s title comes in Debord’s letter of May 9, 1980 to Lebovici. After reviewing the English proofs, the last question remaining was the English title: “The Game of the war” or “The Game of war”? “We must choose the more generalizing and glorious title,” Debord insisted. “Even if kriegspiel = wargame is the most ‘linguistically’ exact, it doesn’t fit at all historically. Kriegspiel connotes ‘a serious exercise by commanders,’ but wargame connotes ‘an infantile little game played by officers.'”

(from http://r-s-g.org/kriegspiel/errata.php)

best, -ag (for RSG)

Steffen P. Walz said,

April 17, 2008 at 3:25 am

dear alex / RSG,

thanks for shedding light on the topic.

so that would be the other exception – that debord indeed did, at least during development, use the pseudo german language term.

yet, i wonder why eventually, debord chose to neither use the german term for the french original publication’s title, nor did atlas press (or translator donald nicholson-smith) opt to use the german term for their english translation of the book, which is, “awkwardly”, you argue, titled “a game of war”. atlas press must have reviewed debord’s letters, too, i would believe, where he had argued for “kriegspiel”.

not only in terms of phrasing, but also in terms of continuity, “kriegspiel”, to me as a native german speaker, feels as awkward as “the game of war” may feel to you. let me get this straight: i do not think your port should be subject to litigation, saying this as an academic and someone who has been rejecting classic copyright law not only in conversation. i can even see that choosing a different, but historically evident and proximate title is an act of “abolishing copyright” in the tradition of the situationists.

in the end, i just find it interesting historically, and noteworthy, that you entitle a game – which aims to be a port of an original tabletop game, the latter which the originators in two languages had chosen to officially call a certain name – with another name, and that the title selected by RSG does connote (and underline) a historical source and basis of the port which, at least title-wise, had only been an inspiration for the original game. although this all may sound like i am standing on trifles, but by choosing a different name, you make an example of how to enforce your will over the will of the established situationist circles;-). vive la revolution!

br,

spw

John Kula said,

May 29, 2008 at 1:24 pm

I’ve been writing an article on A/The Game of War for Simulacrum 28, and my recent research brought me past this site. I apologize for being late.

Charles Swann Roberts designed his game “Tactics” in 1952, about the same time that Guy-Ernest Debord was working on his game. Debord may have been aware of the history of “Kriegsspiel”, and possibly of some of the early-to-mid 20th Century precursors (or missing links) between board games and conflict simulations. But certainly “Tactics” is recognized now by board wargamers as the first conflict simulation. Despite the similarities between their two games, I doubt that either Roberts or Debord was aware of the other and what he was doing, if for no other reason than the different languages and mindsets.

In any event, there are enough board wargames in existence now (over 5,000 by my last count) that use counters with differing characteristics, boards divided into squares or hexagons, and rules relating to the importance of supply lines, that a cease-and-desist order, even only on the name (Avalon Hill also published a game called Kriegspiel), would apply to many more games than simply the RSG port.

Matthew said,

May 29, 2008 at 5:56 pm

Hi John K.,

Thanks for the note. Do you have any hard evidence that Debord was working on the game around 1952? He was born in 1931, so this would have made him very young indeed, and was certainly prior to his political activism with the SI.

In any case, I certainly agree with you that the mechanics introduced by both Roberts and Debord have since found their way into a great many different games.

Matthew said,

May 31, 2008 at 9:33 pm

[John Kula sent me the following response via email and confirmed I could post it here. Especially interesting for the suggestion that Debord may have seen S&T, the General, or some other American wargames “magazine.” MGK]

Greetings Matt,

Many, if not most, of the traditional conflict simulations were designed by

young men in their late teens and early 20s, particularly those published by

SPI in the 1970s.

Prior to the SI, Debord was known to be a Lettrist, and also belonged to S

ou B.

Most discussions I see about Debord’s game state, or imply, that it was

designed in 1977. This was the year that Debord co-created his Society with

Ludovici, and first published his game with entrepreneurial intent. But he

had previously patented it in 1965, which strongly suggests an earlier date

of design. As a game designer myself, I can attest to the difficulties and

time delays inherent in developing a new game system. Debord was doing it

from scratch.

Here are some related references, of the many I have read:

[ 1.] From Guy Debord To Floriana, 25 March 1986

It will be necessary for us to speak of Kessler. Much more intelligent than

the hobby horse of the V.C.R. type that dislodged Marie-Christine, Kessler

understood that kriegspiel is not a question of a plaything, but a game. The

magazines that he sent me confirmed that the Americans had, for twenty years

or more, remained at the same picturesque simulation of an infinity of

precisely historical battles, replayed on different maps with different

unities or technologies, which all want to be ludic figurations of

(equivalent) representations of these particular, already-determined

battles. The French have only tried to translate or imitate this. “The Game

of War” is the representation of battle in general, and even war itself.

[ 2.] Guy Debord believed his war board game would be his legacy BY NATHAN

HELLER

Still, he thought his legacy would rest on something else. “I succeeded, a

long time ago, in presenting the basics of [war] on a rather simple board

game,” he wrote in 1989. “The surprises of this kriegspiel seem

inexhaustible; and I fear that this may well be the only one of my works

that anyone will dare acknowledge as having some value.” Debord invented the

Game of War, as he called it, in his early twenties-he had no military

background-and patented it ten years later. The version that finally reached

market in 1987, after more than two decades, included blow-by-blow

commentary on a match between Debord and his wife, Alice Becker-Ho.

[ 3.] Anarchy magazine

Kriegspiel was created by Guy Debord based on the military strategy of Carl

von Clausewitz. Debord’s first versions of the game were being played in the

50s and it was refined until the rulebook was made (1977), 5 metal versions

were created (and used in the film In girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni)

and, finally, the game was mass produced on cardboard with wood tiles

(1987).

[ 4.] McKenzie Wark

According to Debord’s second wife Alice Becker-Ho, he patented his Game of

War in 1965.

All the best,

John Kula