But There Could Have Been: Possible Worlds Theory and ASL

So the rubble was still settling in the aftermath of some hard-fought actions in the streets of Stalingrad when my adolescent self, lo these many years ago, turned to the fine print at the back of the original Squad Leader rules booklet and read the following in the Designer’s Notes: “Any knowledgeable wargamer will see at a glance that the terrain of SQUAD LEADER has been abstracted to better capture the ‘feel’ of infantry combat. . . . The Dzerhezinsky Tractor Works alone was an immense complex that could not be accurately portrayed by 8 of our city mapboards! Indeed the Germans didn’t succeed in breaking into the Tractor Works until . . . 200! German tanks had assaulted the outer defenses.†Though I had been playing hex and counter wargames for several years and probably instinctively understood that realism was a problematic word applied to dice and cardboard and CRTs, this was the first time I had seen the concept of “abstraction†so unabashedly articulated. Suddenly my team of crack assault engineers storming into the Tractor Works under cover of smoke and HMG fire didn’t seem like such an achievement—the “factory†was only a piddling little cluster of hexes. I played SL and the rest of the series happily for many years afterwards, but that discrepancy always nagged at me. Maybe, I thought, I could get 8 or 10 more city boards and 200 tank counters and make it right?

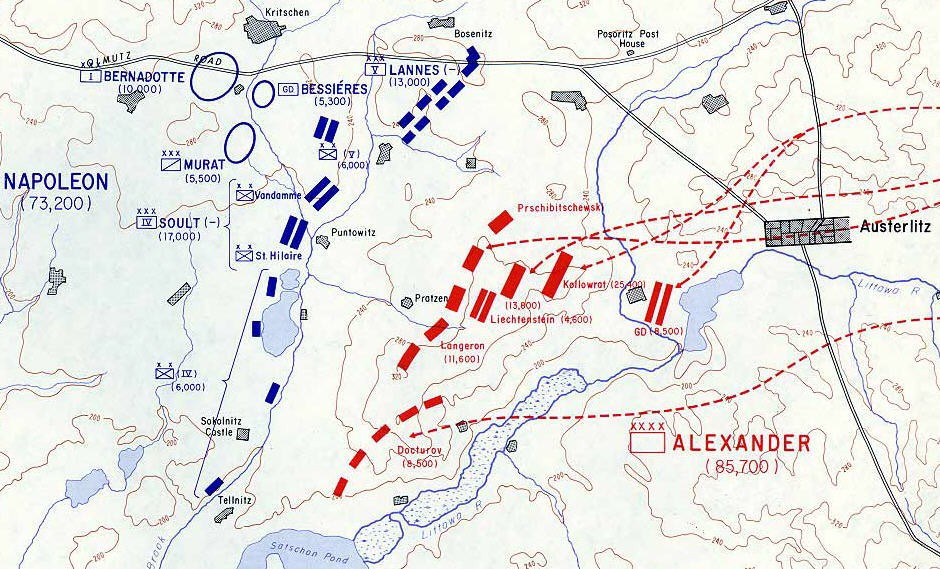

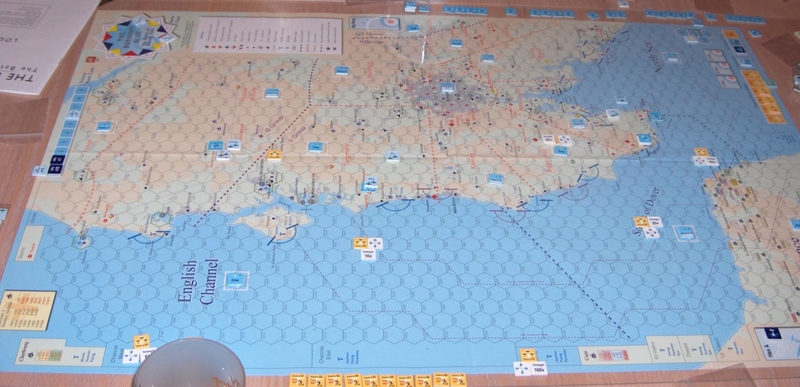

Of course Red Barricades, the first module in the historical ASL (HASL) series proceeded to do exactly that not too many years later. Historical ASL—even the name is telling—exposes some interesting tensions in the game system. Most ASL scenarios are played on generic or so-called geomorphic map boards, whose layouts depict a “typical†village, forest, piece of a city, etc. Despite the fact that the historical basis of the geomorphic scenarios was usually carefully established, the geomorphic map boards themselves—literally the foundation of play—were always a conspicuous abstraction. HASL was, in effect, the game system’s clearest acknowledgement of this phenomenon, substituting depictions of actual terrain (the Red Barricades maps were derived from aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by the Luftwaffle).

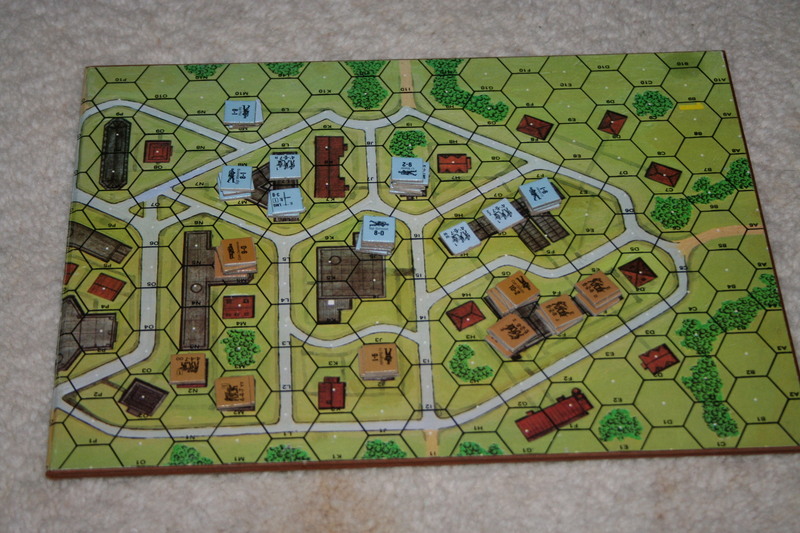

Urban terrain depicted with an ASL geomorphic board (left), Red Barricades (center), and actual aerial photograph of Stalingrad during the fighting.

One of the more brutal and bitter fights that occurred during the combat in Stalingrad in late 1942 concerned a Soviet stronghold that had come to be known as “the commissar’s house.†The ASL system features two scenarios that recreate this particular action, one using the geomorphic boards and one played on the Red Barricades map. Both are ultimately abstractions—the “historical†map includes stone walls whose 60-degree angles follow the outlines of the hex-grid, for example. But some interesting observations can still follow. In particular, I’m interested in whether wargame scenario design can be fruitfully mated with an area of analytical philosophy known as possible worlds theory. Possible worlds theory has in turn spawned applications in domains like narratology. Surely it is relevant to the design of interactive simulations, electronic or otherwise. In particular, I’m interested in thinking about possible worlds theory in relation to immersion or suspension of disbelief. When we play a geomorphic ASL scenario called “Counterstroke at Stonne,†we know that board 3 isn’t meant to be the small French village of Stonne, not exactly . . . but it could have been, and at a certain point we’re willing to suspend disbelief. Using a desert board, by contrast, would certainly be enough to break the illusion as would a major geographical feature like a river. But what about the chateau that’s depicted on one of the geomorphic boards used in the scenario, which, the story goes, is there because the designer read about a “chateau d’ eauâ€â€”a water tower. Whoops. A glitch, but one that has no real impact on the integrity of the scenario—after all, there could have been a chateau just outside the rural French village of Stonne, right? Had the false chateau appeared in a treatment of the battle based on actually terrain (like Red Barricades did for Stalingrad) it would have been regarded as a far more serious matter. But given that all such maps are still ultimately abstractions, how then can we account for the difference? Can possible worlds theory help here?